What do you want me to do for you?

He's listening for your answer

“What comes into our minds when we think about God is the most important thing about us.” A.W. Tozer

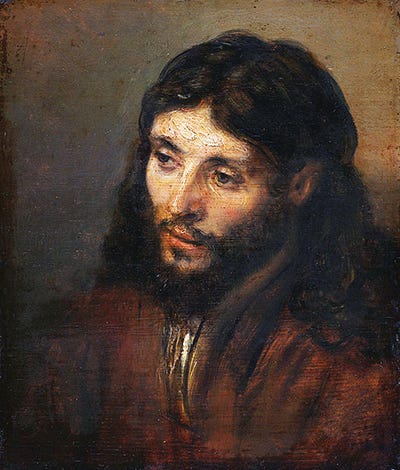

Notice his eyes, weary yet focused—utterly undistracted. Feel his kind attention probe beneath rehearsed intention, to the shame or shaky confidence of the child still hiding within you.

How often I long to be looked at this way. Or, more than looked at, be read—measured, truly seen, forgiven, sent on my way with a lighter step, a cleaner heart.

His lips are slightly parted, as if about to say, with quiet conviction, I see you, I know all about you, I forgive you, I can heal and free you. Will you trust me? I can cure your willful blindness, I can make you into someone astonishingly new.

Certain I need more power

In Mark 10, two types of people approach Jesus. First, two of his disciples and (according to the same story in Matthew) encouraged by their helicopter mom. Second, a blind beggar, sitting by the side of the road, with only the usual crowd for company.

In both cases Jesus will ask, “What do you want me to do for you?"

I assume the author of Mark had his reasons, placing these two scenes from the ministry of Jesus next to each other. Perhaps to teach us something about the characters? Perhaps to point to something in us?

James and John, well known to Jesus, approach him boldly, “Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask.”

My first impression? Arrogance! Too bold, too sure, too demanding, too selfish, too much this and too little of that. Maybe my response provides a window into my Scandinavian-American upbringing. Maybe my response is what the author intends…for the moment.

Surely Jesus is going to put them in their place.

Yet, I turn the page to Mark 11 and read the promise James and John no doubt heard again and again, “Whatever you ask for in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours” (verse 24).

The two brothers had the right to be a bit audacious—they are taking Jesus at his word.

In the Matthew version of the story (where the mother, and aunt of Jesus, does the asking), the other 10 disciples are furious when told of James and John’s presumption. Perhaps they were mad at themselves for being too pious and unselfish themselves. Like, being a step behind the sibling who yells, shotgun.

Scroll back to Rembrandt’s painting, where Jesus turns to a person off-screen. Eyebrow raised, head cocked, he looks deeply into someone’s yearning heart—yours? The brothers’?

Then Jesus asks the crucial question, “What do you want me to do for you?” James and John glance at each other, and then quickly back at their mom, who nudges them along. Did the brothers answer in unison? Did their words, well-rehearsed, tumble over each other? “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.”

Crickets.

A bit of context: As far as the disciples knew, this long-promised Messiah (Jesus) had come to defeat the Romans and restore the throne of Israel. Logically, the closer their position to this soon-to-be king, the more important and influential they would be.

So very typical, so predictably human. Point to any successful, popular person—celebrity, politician, rockstar, whatever—and you’ll see an entourage jostling for position, as if greatness is contagious. And least-ness is the worst fate of all.

In answer to the disciples’ request, Jesus seems to change the subject.

Certain I need more mercy

A few verses later, Jesus meets Bartimaeus, blind and begging by the side of the road, annoying the crowd with his cries. Jesus invites the wretch to come close, and again asks the question, “What do you want me to do for you?” Bartimaeus simply replies, “Rabbi, I want to see.” “Go; your faith has made you well,” is Jesus’ short reply. And just like that, the man can see—a prayer is answered efficiently, exactly as we expect it to be.

What are we to learn?

Back to James and John. Read as a stand alone story, we could deem it a cautionary tale. In Matthew’s parallel telling, Jesus rebukes all the disciples, reminding them they’ve latched onto a tired old trope—leaders, religious or otherwise, using Jesus as a mascot to gain influence and power, to dominate others.

Yeah, that preaches.

But, where Jesus is truly Lord, the great will be those who serve. The first will be the least, as Jesus gladly chose to be.

In addition, Jesus reminds James and John, “You do not know what you are asking.”

And, often, neither do we. Have you ever caught a glimpse of an alternate outcome—where you’d be if you had gotten your way? By the grace of God, your foolish wish, a bent desire, a longing better left ignored, was thwarted—do you breathe a sigh of relief?

Too often we are the last to know the thing we really need.

Later in the book of Mark, two men were chosen to take their place on Jesus’ right and left. The cross revealed his glory, and two random bandits shared his fate. Though James was spared that particular path to glory, he was executed for his faith by King Herod Agrippa (Acts 12:2), and John lived to the end of his life in exile.

But, in a strange way, their bold request was granted. Thousands of years later, we still mention their names wherever Jesus is adored. Schools, hospitals, great cathedrals bear the names St. John or St. James. Their example and words are closely studied—proximity and glory indeed.

Sometimes Jesus answers prayer by flipping our assumptions, by turning us in a new direction, and we end up where we wanted to be all along.

The head of Christ

Rembrandt painted this Head of Christ, in 1648. Commonly, artists emphasized Christ’s deity, using halos, numinous garments, the glowing beauty of an AI-like, manufactured ideal. But Rembrandt chose to paint from a live model, probably a Sephardic Jew from his neighborhood in Amsterdam. As a result, we see Jesus depicted as human, relatable, ordinary—one of us, for us.

I’m reminded of a portrait that hung on the wall of the lobby in my childhood church. The framed print pictured Jesus, flooded with light, his long softly curling hair as shiny as the old Breck shampoo ads. His eyes were cast solemnly upward and no matter how long I peered at his pious pose, I never felt like he, in turn, peered at me.

How do you imagine Jesus—if you think of him at all? Some who knew Jesus in the flesh described him in these ways:

Son of man lamb of God who was slain, bread of life light of the world the good shepherd man of sorrows and acquainted with grief Immanuel (God-with-us) friend of sinners the way, the truth, and the life the Alpha and Omega, beginning and end of everything

Look at the painting again—which description do you think was on Rembrandt’s mind?

When Christians portray Jesus as aloof perfection, or as a table-toppling alpha avenger, we are projecting onto him our own, self-righteous lust for control.

When I meditate on the painting, and then on Mark 10, I’m left with two words:

Just come…

your heart broken into pieces, or filled with boastful visions—either way he waits patiently for you. He already knows what you’ll say, and will never turn you away.

Your faith will make you whole

“O dear child! The best possible life is this: to do our utmost to content God with love, and above all to trust in him. For we come closest to him by confidence; for true prayer is nothing else than pure abandonment to him, with perfect fidelity to trust him in all that he is….” Hadewijch of Antwerp, 13th century poet

I love the parallel between the thieves and the disciples on the left and right of Jesus. I am teaching on service in November--this has is helpful in framing my thoughts. I am also challenged think about how I picture Jesus. Too much distance I think.